When we think of the journey of electronic products, most of us are probably thinking about the journey that our new washing machine takes from the shop and worrying about getting it up the stairs and into our flat. Very few of us will be thinking about miners toiling away far below the surface, the Earth’s resources being used up, or the carbon footprint of every kilometre that a product travels before it eventually ends up in our household. This shows us how sustainability in electronics has to be promoted and approached from many different angles.

Melanie Jaeger-Erben is the head of transdisciplinary sustainable electronics research at Fraunhofer IZM and the Technical University of Berlin. She shares some of the visionary strategies and innovative research in an interview with RealIZM.

Why is sustainability so important in electronics?

Melanie Jaeger-Erben: On the one hand, the makers of electronic devices create something of value for the market and for ourselves, the consumers. The other side of the coin, however, is the vast social and ecological damage this entails. Mining and the depletion of resources hurts our environment, and so many of the workers in the electronics industry have to cope with very poor working conditions. Some metal ores are mined in warzones or conflict areas, and mining indirectly finances social conflict.

Throughout the so-called value chain of a product, emissions are a massive problem, and this applies no less to the making of electronics products or their shipping around the world. Eventually, they end up on the market and in our households, and then we see that many of them, particularly ICT devices, are not used for as long as they could be. The fact that the greatest social-ecological damage is caused during production means that the longer a product is used, the better its environmental performance: The longer a product stays in circulation, the less pressure is exerted on resources. In the ideal case, a product would be used for a long time in its first life, used second-hand in its second life, get refurbished or upcycled for a third and fourth life, and eventually end up in recycling to recover the materials in it.

What is the best way to ensure durability?

Melanie Jaeger-Erben: Durability is influenced by many factors, including the product’s reparability, long-term functionality, and technological longevity. For them to be truly durable, products must be designed in such a way that the user actually wants to keep them. They need a design that wears out as slowly as possible, and people must be able to maintain and look after their devices properly.

We can consider this in functional and technological terms: How can you produce quality products that are robust and reliable? As far as reliability is concerned, Fraunhofer IZM is naturally one of the leading research institutions. In our Environment and Reliability Engineering department, we are trying to combine the technological expertise with the socio-scientific, economic and political perspectives to understand the requirements for durable and sustainable products.

Can you explain the term “lifetime” in relation to durability?

Melanie Jaeger-Erben: The lifetime of a product is defined as the period from the moment a product is made to the moment it fails, i.e. when it is functionally so outdated or broken that it can no longer be used and only be recycled. We call this “product death”, since the product’s life ends irreversibly. In this respect, we mainly look at the technological and functional characteristics of a product.

The lifetime of a product must be distinguished from its use time. The use time is the phase in which a product is actively used. For the use time, we have to consider the interaction or relationship between a user and their product. Besides the technological and functional characteristics, social and cultural aspects come into play. A product might, for example, be replaced because it no longer satisfies the needs of the user and another product is more attractive.

Durability refers to the lifetime of a product. A product is durable until the product is, so to speak, dead. That means: it can no longer be used in its originally intended form. A smartphone is made for communication, information, and entertainment. If it can no longer do any of that, then it is no longer durable. But users can also place the product in a “coma”, that means: It could be used, but it simply is not used. A lot of working smartphones are nowadays relegated to spending their lives in drawers because their users bought newer models.

What determines the reliability of a product?

Melanie Jaeger-Erben: At Fraunhofer IZM, products are tested for material reliability, among many other factors. This means finding out to what extent defects and faults can arise during their use that affect their lifetime. What is becoming increasingly important, however, is software-related obsolescence. This can happen when software and hardware interfaces are no longer functioning. It may happen that a product’s hardware is still functional, but the software has become so advanced and complex that the hardware can no longer keep up. Or the software is not secure enough, and a virus kills the entire system.

In terms of material reliability, you have to strike a balance between practicality and reliability. If you make everything in a smartphone extra durable and reliable, then the phone would probably be much thicker in the end. Users might not like that, because it would be too heavy and uncomfortable to carry.

What impact would the production of durable products have on our environment?

Melanie Jaeger-Erben: If you manufacture products that are more durable by using spare parts or particularly high-quality materials, this usually means using more expensive resources in the product’s original manufacturing. The product’s environmental performance is actually worse at the point it comes into the market. The product must then be used for a long time to really benefit from its better quality, reliability, and durability. Durability only makes sense if the product is used for a long time in the end. That is why social factors are important too: you can make the greatest products in the world, but you gain nothing if people feel the need to buy a new phone every two years, because they think they need to keep up with changing technology. It must at least be good for second and third-hand use.

Are there any defined standards or values to be achieved in the field of durability?

Melanie Jaeger-Erben: Manufacturers and product developers plan for a certain lifetime and design the product accordingly. You can expect that manufacturers want to at least meet their warranty requirements for the two or three years that matter. However, of course, this cannot be predicted exactly. Users expect their devices to last longer than guaranteed. Warranty periods are one type of standard, which is defined nationally. Then you have very powerful regulation coming from the EU: There is, for example, the European Ecodesign Directive. Fraunhofer IZM is involved in a European research project on standards and procedures to test premature obsolescence. There is also a demand for lifetime labels or lifetime specifications to be placed on products, but this does not exist yet.

How can the required durability be achieved?

Melanie Jaeger-Erben: Right now, monetary value is mainly generated by product sales. It is all about selling a product with a certain image, a certain functionality, or a certain promise. Current business models need to be transformed for us to be able to make longer durability an economically viable factor.

That is why we are researching business models that encourage companies or manufacturers to invest in their products’ longevity. This can be achieved, for example, by offering products for rent or lease, instead of selling them, or by offering the services of a product, instead of the product itself (the service of laundry, instead of the washing machine as a product). As soon as products remain the manufacturers’ property, and it is their responsibility to ensure that the products work, manufacturers will naturally be more interested in making them as durable as possible. This already works very well in the B2B market.

It is, of course, also important to incorporate ecodesign criteria into the product design and production. In this respect, we are also investigating options and forms of user integration into product development.

Testing is also important: How can you identify certain weak points in the durability from the outset and develop strategies to counter them? Another question is also which design concepts, like modular design, are useful for replacement, repairs, upgrades, etc. As regards the use phase, different forms of use need to be considered, such as why some users maintain and repair their equipment, while others prefer to buy new.

Then, at the end of the value chain, it is about creating interfaces between manufacturers and recyclers.

There are many starting points and the important thing is to consider these points holistically. Of course, recycling is good, but at the same time, you have to rethink the design process and perhaps try to change something with the consumers themselves. A holistic approach is needed to initiate and motivate truly profound change.

Where do we stand then?

Melanie Jaeger-Erben: This is very difficult to answer generally. I have a very subjective view and look at it from a socio-scientific perspective.

However, there are two developments. On the one hand, there is ‘business as usual’: many products are constantly thrown onto an already packed market; marketing strategies aim to sell consumers something new as quickly as possible. If you look at how quickly the electronics trade exchanges its products, the focus is still on “more, faster, and newer”. This logic remains very strong, and it is difficult to overcome old ways of thinking. Old habits die hard.

On the other hand, there is also a certain sense of unease with this ‘business as usual’. Industrial or post-industrial societies will reach the limits of growth. Innovation cycles could not get any shorter; resource availability is an increasingly difficult issue; waste and electronic scrap recycling is getting more and more energy intensive. It is becoming increasingly clear that things are not going to continue like this, and many companies are certainly feeling the effects already. So, there is a growing interest in circular economy approaches and the idea that we may actually need different business models.

In a finite world, there is no such thing as infinite growth. The interest in the circular economy brings together a large number of players, which could result in a great network or movement. The circular economy has strong political support, especially on the EU level, where there are many initiatives for creating appropriate framework conditions and regulations. Guidelines on reparability and new standards in eco-design are coming; these are all signs of change.

How many companies already have a philosophy of durability?

Melanie Jaeger-Erben: I would say that this is still a niche area. I think many large companies are sending out feelers in this direction, which could later be expanded upon if they prove successful. A few companies are pursuing certain business models, such as rental options for equipment or household appliances, or they provide vehicles for car sharing. However, the companies really dealing with the idea of the circular economy are mainly smaller start-ups.

How do you feel about this in the smartphone market?

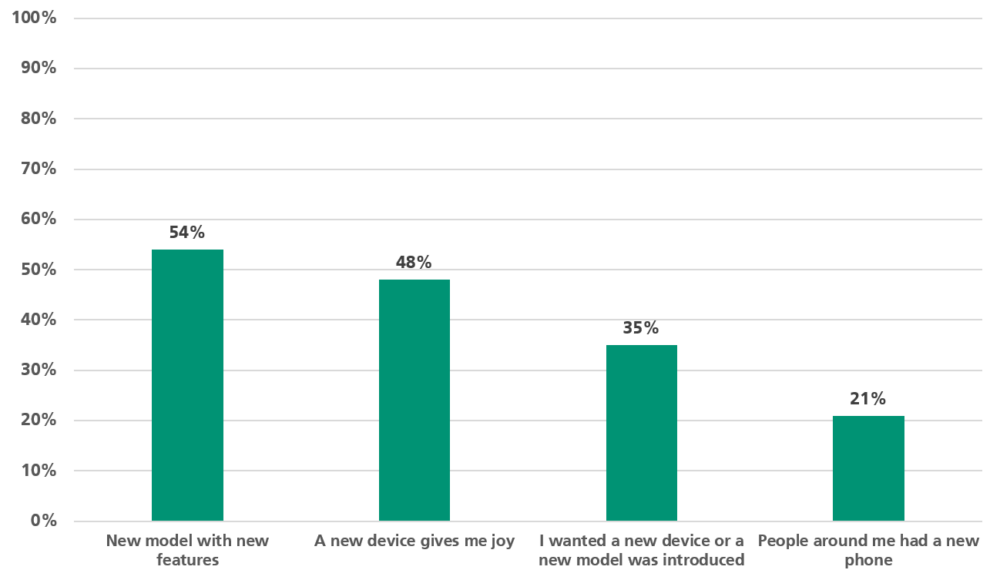

Melanie Jaeger-Erben: In the case of smartphones, the average use time is only two to three years. Most devices would last longer, but they are replaced even if they still work just fine. This is influenced by trends and tastes, but also by structural forces, like mobile phone contracts promising a new phone every two years. When a new generation of smartphones enters the market, many consumers have the impression that their current smartphone is now obsolete or, at least, outdated. Since many users don’t have much knowledge about the technical characteristics or functionality of electronics, they fall prey to the assumption that the latest model would be the best model, just to be on the safe side.

So we have two options: Making people more aware and informed, or making devices more durable. What do you think has to happen first?

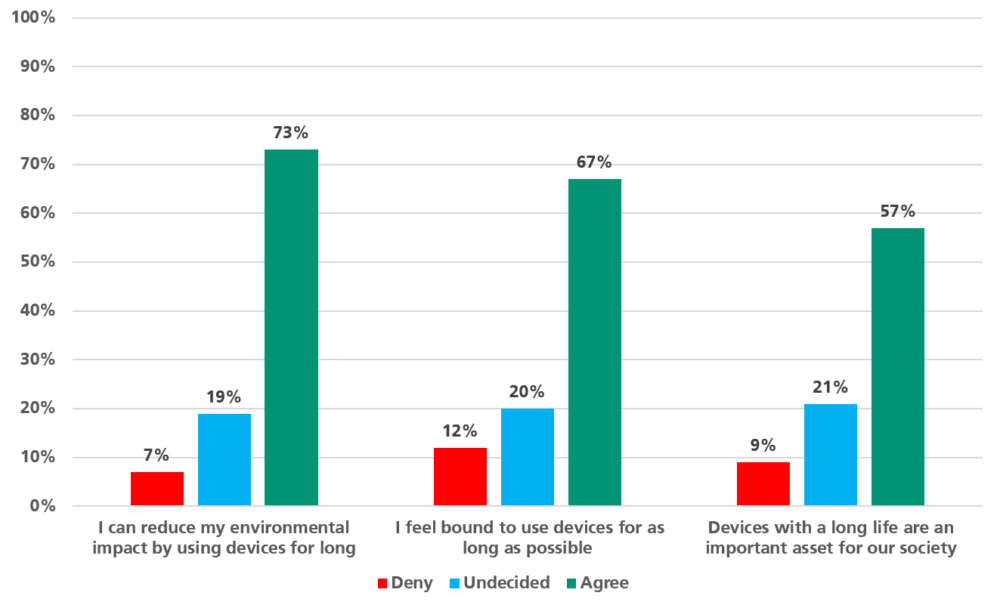

Melanie Jaeger-Erben: In any case, both must happen. There must be a general agreement in society that the things we already possess should be preserved. This is about a general appreciation for the value of resources: from manufacturers, who benefit from cheap resources and who create value, but primarily for themselves. But also from consumers, who have a responsibility to make the most out of the resources used for their products.

Of course, this is difficult when there are 200 different models of televisions available at every big box store. The promise is abundance, not scarcity. This disregard for resources and literally for the blood and sweat of workers must change.

Your research group conducted a survey about this. Can you tell us about what you found?

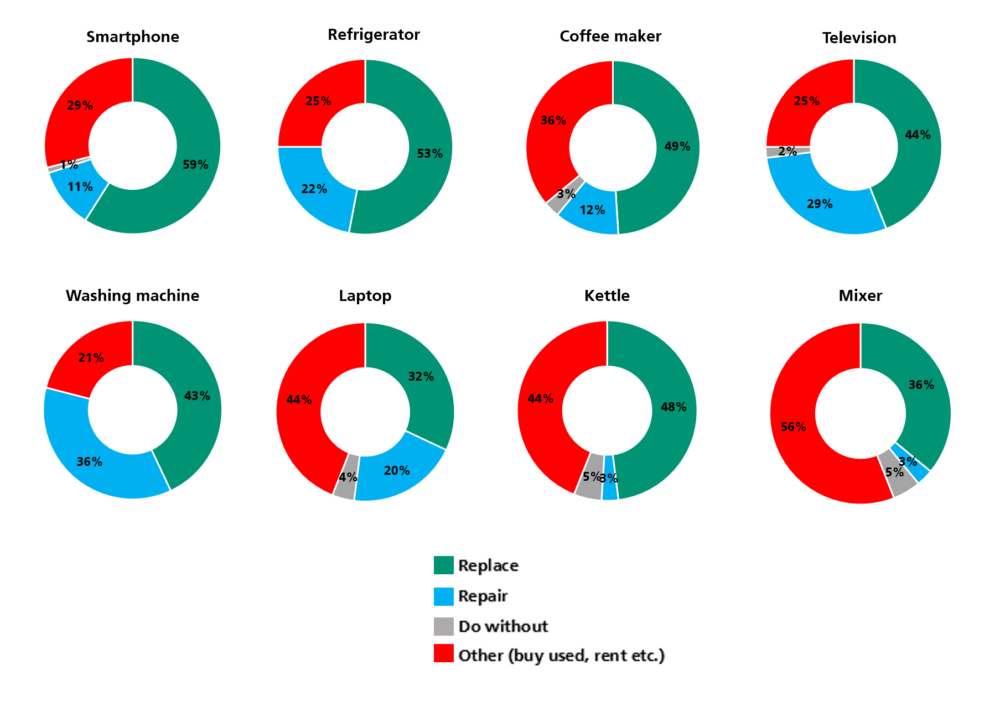

Melanie Jaeger-Erben: The reported use of equipment – relating to previously owned equipment – show that there may indeed be a trend towards longer use. For example, a comparison with a survey we conducted in 2017 shows that the useful lives of smartphones have increased slightly. Nevertheless, many new purchases are not motivated by older device breaking: 67% of people buy new smartphones and 35% new washing machines, even when their old devices are still working. The reasons for this are manifold, but a comparison of the devices makes things clearer: Especially with smartphones, there is a strong desire to be up-to-date, and people are tempted by the newest deals.

When something unexpectedly breaks, which is normal for most people owning a range of devices, the easiest thing to do is to buy a new device immediately. Only a third of all people would consider repairs, and again only some appliances, such as washing machines or television sets.

You can find more information in our photo gallery:

Are there any global initiatives to regulate durability?

Melanie Jaeger-Erben: If you look at reports by global players like the World Economic Forum or the different sections of the UN, they all agree that we have a problem with resource conflicts or electronic waste. They all underline the importance of a transformation towards a circular economy. There is global awareness of the problem. Even though it may not directly address the lifetime of products, it is about sustainable production and consumption. Almost the entire world has signed on to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), and every country has a duty to implement them and develop a monitoring system to document progress.

What can national policy makers do?

Melanie Jaeger-Erben: Any country could be a pioneer. If, for example, Germany leads the way as a pioneer in the automotive industry, many people could take their lead from it. It was a similar story with the big energy turnaround: Germany set the benchmark that many other countries found interesting. You can spark a race to the top and hope that as many other countries as possible will follow suit.

Can you tell us more about some of the current projects at Fraunhofer IZM?

Melanie Jaeger-Erben: There are so many, but we specifically have the research group ‘Obsolescence as a Challenge for Sustainability’ in cooperation with TU Berlin, where we are looking from different angles at strategies against obsolescence. In another project, we are focusing on modular smartphones and how this new technological solution might promote sustainable consumption and production.

We now have a new project on software obsolescence in the works. The aim is to look at how the different pace of development of hardware and software leads to product obsolescence, because software develops faster or security problems arise through software. The EU-project on premature obsolescence I already mentioned.

There are also several projects on eco-design and how to bring eco-design strategies into practice. But many more projects at Fraunhofer IZM relate in some way to the issue of circular economy.

Like!! Thank you for publishing this awesome article.