Worldwide, the consumption of electronic devices – from smartphones and refrigerators to cordless screwdrivers – is rising steadily, as it is for clothing. In 2022, every European bought an average of around 19 kilograms of textiles and threw away about 16 kilograms of them.1 In addition, each EU citizen produces around 11.2 kilograms of electrical and electronic waste every year. In 2022, about 14.4 million tons of electrical and electronic equipment were sold in the EU, and 5 million tons of e-waste were collected.2

Consumer demand keeps growing, and an increasingly diverse range of products is hitting the market. However, the share of sustainable, repairable, and recyclable products is very low compared to the figures for products sold in the market. Circularity was 9.1 percent in 2018, 8.6 percent in 2020 and down to 7.2 percent in 2023.3

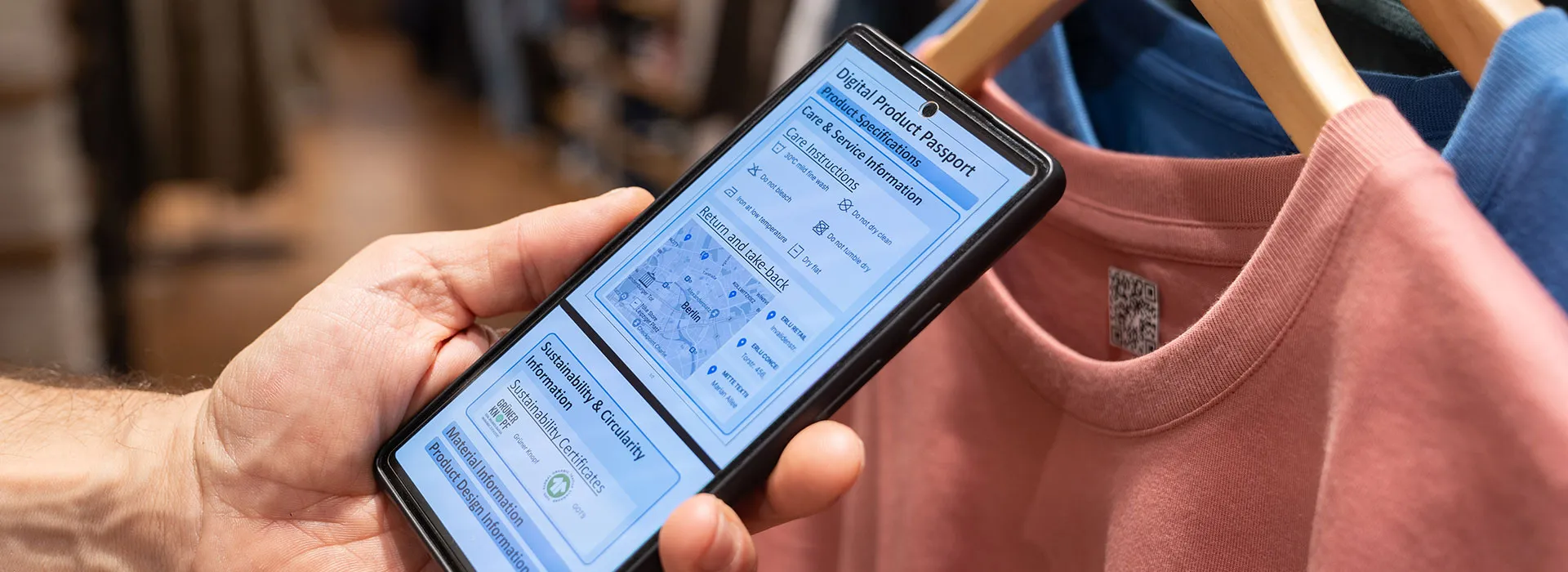

To promote the production, use, and recycling of recyclable consumer goods, the European Commission plans to introduce digital product passports (DPPs). The aim is to make the environmental impact of products more transparent and make products last for longer.

The DPP was first mentioned in the EU Green Deal in 2019 and is part of the Sustainable Product Initiative. The ecodesign requirements include durability, reparability, and recyclability as well as information on the carbon footprint and the threshold levels of substances of concern, plus information about resource efficiency and recycled content.4

In 2023, the proportion of secondary materials that were returned to the circular economy after their useful life was 7.2%.3 | © Fraunhofer IZM

From linear to circular business models: Digital product passports can be the key for reuse and recycling

Digital product passports are designed to provide comprehensive information to help consumers, manufacturers, repair services, and recycling companies make informed decisions. Recycling companies receive important data on valuable and harmful substances, which is crucial for efficient recycling. And consumers benefit from specific information that helps them make informed decisions about the care and repair of their devices.

The DPP should not only contain static data from the time of the product’s manufacture, but also offer a way to collect data on use and maintenance over the entire lifespan to create a complete »résumé« of a product. In order to be used by the various actors, the DPP must meet technical requirements: The information it contains must be structured, machine-readable, and searchable. The DPP can be thought of as a transport container that collects and passes on all this information.

Roadmap for implementing the DPP | © Fraunhofer IZM

Need for research

The DPP is still in the works. The CIRPASS research project (Collaborative Standardization of a European Digital Product Passport for Stakeholder-Specific Sharing of Product Data for a Circular Economy), which ran from 2022 to 2024, played a key role. Its aim was to lay the foundations for the introduction of digital product passports in the European Union. The project defined product groups to be regulated first and developed the information and technical architecture of the DPP.

Batteries will be the first product group for which a DPP will be mandatory in 20275, followed by over 30 other product groups in the years to come. The priority product groups include textiles, furniture, toys, and electronics.

The environmental experts for electronics at Fraunhofer IZM were also part of the discussions with over 40 stakeholders, including representatives for production, retail, repair services, and consumers. Fraunhofer IZM has many years of experience in life cycle assessments for electronic products and advises companies on creating digital product passports and meeting ESPR requirements.

Together with the project partners, various use cases in the three priority sectors – batteries, electronics, and textiles – were analyzed on a qualitative level. The aim was to identify the advantages and obstacles to the use of the DPP. In addition, the project team wanted to understand which technical modules are useful, how such a system should be designed holistically, and what information it must contain.

The follow-up project CIRPASS-2 was launched in 2024. In the three-year project, DPPs are tested in practice by implementing use cases for the circular economy in the value chains of textiles, electrical and electronic devices, tires, and building materials.

»For these product groups, indicators such as durability, reparability, and recyclability are evaluated in terms of their environmental impact,« explains Eduard Wagner, sustainability expert at Fraunhofer IZM. »Depending on the product and application scenario, the indicators have to be weighted differently.« Disposable textiles such as breathing masks must, above all, be recyclable. Other products, on the other hand, must be durable, but not necessarily reparable.

To determine the environmental impact, the Fraunhofer IZM conducts impact assessment studies as part of CIRPASS-2. The focus is on energy-consuming end user products like washing machines, refrigerators, and air conditioners. »We are also looking at industrial electrical equipment such as large washing machines and dishwashers to determine whether they need a digital product passport (DPP) and what the requirements are. Whether these devices will receive a DPP is still undecided,« Wagner explains.

Sustainability as a competitive advantage

The need for information is constantly increasing. Eduard Wagner explains: »The major electronics manufacturers are proactively preparing for the DPP.« Currently, the questions that the environmental experts for electronics at Fraunhofer IZM receive are mainly about preparing employees for the topic of ecodesign and less about life cycle assessments.

Wagner emphasizes that now is the best time for manufacturing companies to prepare for the DPP. In doing so, they should consider how they can improve their products, what information will need to be provided in future, and how they will adapt to this. Manufacturers that address these issues early on and demonstrate their sustainability credentials can gain a competitive advantage. This also includes how to make electronic products more durable and recyclable and how to communicate this.

Focus on value chains: Sharing information between actors

The various actors along the value chain of electronic products should share information in the form of a DPP. This includes both material producers and product manufacturers as well as recyclers. The DPP should not only be viewed by the various actors, but should also be readable by machines and application systems.

The harmonized and comparable data should enable sustainable purchasing decisions. Consumers should also benefit from information about their products’ use, maintenance, and repairs during their working lives. For proper waste disposal or recycling, information about the origin and composition of the materials as well as possible reprocessing should be made available.

Actors along the value chain | © Fraunhofer IZM

Data collection challenges: environmental protection versus data protection

Not all products are suitable for the DPP. In the first phase, the flow of information will be in one direction only: from companies to their consumers. To develop new circular business models, data about users’ behavior would be helpful for re-commerce companies, for example information about the time of purchase, the first day of use, and the time of the product’s first failure. However, collecting this data is challenging and requires the consent of the consumers as to which data may be collected and processed. How this can be done still needs to be resolved.

A balance must be found between the benefits for companies and the protection of consumers. »The environmental benefit, consumer protection, and economic advantages for companies are analyzed in great detail in the preliminary studies for the DPP in order to design sustainable and environmentally friendly products. However, as soon as usage data becomes personal, strict exclusion criteria apply,« says Wagner, summarizing the challenges of considering environmental impact versus data protection.

The nuts and bolts for transparent product and environmental information

The DPP must contain certain types of information and be accessible electronically via a data medium, e.g. a QR code label or RFID chip. That medium must be affixed to the product, its packaging, or the documents accompanying it. Although the DPP does not have to be attached before the product is sold, it should already contain information from the suppliers.

For environmental information and the carbon footprint to be accessible, various data must be collected along the entire value chain. Most of the information has to be provided by the manufacturers, for example, on the sustainability of the ingredients, the countries of origin of the materials, and the reparability and recyclability of the product. This data is relatively easy to collect.

»However, a detailed life cycle assessment is difficult, because information about processes and energy or material flows at the beginning of the value chain is often not readily available, leading to gaps in the data,« says Wagner, explaining the challenge of tracking the complex supply chains in detail. Which processes were used in the extraction of raw materials and in manufacturing, which materials and resources were required, and which transport routes and modes of transport were used? In addition, changes in suppliers, product diversity, and process diversity make identification more difficult. In the long term, central data sets should be provided for calculations. National or EU databases are under discussion.

It would be important to investigate which technologies and processes can contribute to the security and trustworthiness of supply chains. This could improve data collection during production and in the upstream supply chains and thus also support digital product passports.

Before the DPP for electronics is introduced, the following questions need to be answered in addition to data collection: Which method(s) are used to calculate the carbon footprint? How are durability, reusability, reparability, and recyclability determined? How is the recyclate content in products verified? What material information is important for recyclers to distinguish recyclable materials from pollutants?

In addition, data management must be regulated. Assigning identification numbers and controlling the amount of data is possible in principle. General information could be recorded in a uniform dataset for all products, while individual pieces of data, such as repair records, could be documented in separate datasets. Questions regarding the storage of data, its form, security mechanisms, identification of information, access rights, and the comparison of data using certain standards still need to be answered.

In addition to these content-related requirements, the DPP must also meet certain technical requirements. The technical infrastructure for the DPP is based on eight modules that serve as a framework. The necessary standards will be developed by the end of 2025; only then can the DPP be actually constructed. The contents will be defined later in the delegated acts.

Circular business models: How repair histories could change the market

The individual recording of the usage and repair history of electrical appliances could open up new vistas for manufacturers. For IoT-enabled devices, usage cycles could be documented and maintenance services offered automatically as needed. For example, a washing machine could display the message »contact customer service« when a fault occurs, in order to arrange an appointment with a technician.

There is also great potential in the secondary market. However, implementation requires a careful decision for each product group in order to maximize benefits. Re-commerce companies could use the DPP to track how often a device has been used, such as battery charging cycles or the number of washes in a washing machine. This information would help to better estimate the resale value of used products. Sellers also benefit, for example, from being able to determine the optimal time to sell a smartphone based on charging cycles and battery capacity in order to get the best possible price.

Additionally, companies that refurbish electronic products could target and efficiently address repair needs. Documenting repairs made during initial use could increase market value. For example, replacing the motor in a washing machine could increase the value of the appliance.

CIRPASS 2

Duration: 05/2024 – 04/ 2027

Grant number: 101158775 — CIRPASS-2 — DIGITAL-2023-CLOUD-DATA-04

Project website: https://cirpass2.eu/

Project partners: AOC Innovation, Arcelik, ASCDI, atma.io, BIOIS, circ.fashion, CIT, Cobuilder, CEA, DDCC, Digital Europe, E Circular Aps, Eon, Energy Web, Extra Red, F6S, FJBE, FINATEX, Fraunhofer, GEC, Gorenje, Global Textile Scheme GmbH, GS1 in Europe, Innovalia, IOXIO.io, Kezzler, maki Consulting GmbH, Michelin, MWX, Obada, PIA, PTB, Scantrust, TalTech, Textile Exchange, TNO, TripleR, VDE, whatt.io., Wordline France and ZVEI e.V..

The innovation project is funded by the European Commission’s Digital Europe program.

CIRPASS

Duration: 10/2022 – 03/2024

Grant number: 101083432

Project website: https://cirpassproject.eu/

Project partnery: BAM, CEA, Chalmers Industriteknik, Circular Fashion, DKE, Digital Europe, E Circular Aps, Energy Web, ERCIM, F6S, Fraunhofer, GEC, GTS, Global Battery Alliance, GS1 in Europe, Innovalia, InnoEnergy, iPoint, Politecnico Milano, RBA, RISE, SLR, SyncForce, TalTech, Textile Exchange, TU Delft, Veltha, Wuppertal Institut and Worldline Mint.

The CIRPASS project was funded by the European Union.

Sources:

1 EEA Briefing (03/2025): Circularity of the EU textiles value chain in numbers

3 Circle Economy. (2023). Circularity Gap Report 2023. Circle Economy.

4 REGULATION (EU) 2024/1781 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 13 June 2024 establishing a framework for the setting of ecodesign requirements for sustainable products, amending Directive (EU) 2020/1828 and Regulation (EU) 2023/1542 and repealing Directive 2009/125/EC. Article 5 Ecodesign requirements

Add comment