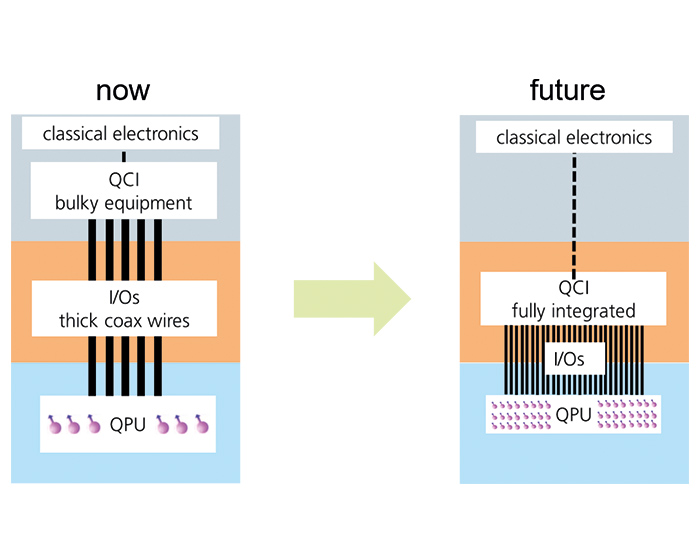

Quantum computers use superposition and entanglement to perform many calculations simultaneously, opening up new solutions to highly complex problems. The control electronics of current cryostats still fill entire floors. In the long term, the aim is to integrate all of this in the cryostat, occupying just a few square centimeters of space. In the joint research project »QSolid,« Fraunhofer IZM-ASSID, Fraunhofer IPMS, and GlobalFoundries are developing packaging technologies to thermomechanically stabilize the wiring of tens of thousands of superconducting qubits.

Steffen Bickel, research associate at Fraunhofer IZM-ASSID, has met RealIZM to speak about the physical principles behind the quantum computers of tomorrow, the status of qubit technologies, and the challenges that come with developing interposers.

»Quantum computers solve mathematical problems in a way that’s different to digital computers,« explains Steffen Bickel, research associate at Fraunhofer IZM-ASSID. »The best way to imagine this is to think of a maze. To get from A to B, we are faced with the choice of trying out one of the possible paths at each junction. A quantum computer is able to take all these paths at once and immediately identify the best one.«

What basic physical principles need to be considered in quantum mechanics?

»Quantum computing is not about solving problems that we use our current computers for, but faster, better, or more efficiently,« explains Bickel. »In fact, quantum computers are being built to simulate complex tasks like the behavior of 20 interacting electrons in a molecule.« The fundamental phenomena at work in quantum mechanics are superposition and entanglement.

Superposition is a fundamental principle in physics and mathematics that states that, in a linear system, the totality of the effects is equal to the sum of the individual effects. In quantum mechanics, it means that a particle can be in multiple states at the same time until a measurement is made.

Entanglement describes the state in which two or more qubits are connected to each other in such a way that they can only be described as a group and no longer individually. Entangled qubits behave either in unison or, indeed, in diametrically opposite ways. Albert Einstein once described quantum entanglement as »spooky action at a distance.« It is entanglement that makes quantum computing possible.

It remains to be seen which quantum technology will prevail on the market. Each qubit technology has its own requirements. The ambition is to entangle tens of thousands of qubits with each other in the long term and to be able to control quantum chips, for which concepts are currently being developed. The »QSolid« research project focuses on superconducting qubits. The electrical connections between these qubits require superconductors.

Superconductors are materials that exhibit zero electrical resistance below a critical temperature.

A spin qubit (semiconductor qubit) is a qubit that uses the spin of electrons to encode quantum information. This can be the »spin-up« or »spin-down« state or a superposition of both to represent the states 0 and 1 of a qubit.

Why spin qubits operate at the Kelvin scale and superconducting qubits at the millikelvin scale

»It is important for the semiconductor industry to get spin qubits up and running. However, only a few semiconductor qubits have been able to be entangled with each other so far. With superconducting qubits, we can already couple more than a hundred,« Bickel says about the current state of development.

Extremely low temperatures are required for functional spin qubits and superconducting qubits. For superconducting qubits, 10 to 20 millikelvin is ideal. Semiconductor qubits already start functioning at 1 Kelvin, giving them the moniker »hot qubits.« »The difference between 20 millikelvin and 1 kelvin may seem small, but in fact, it is a temperature increase by a factor of 50,« explains Bickel.

From room-filling »cable harness« to monolithic control platform in cryostat

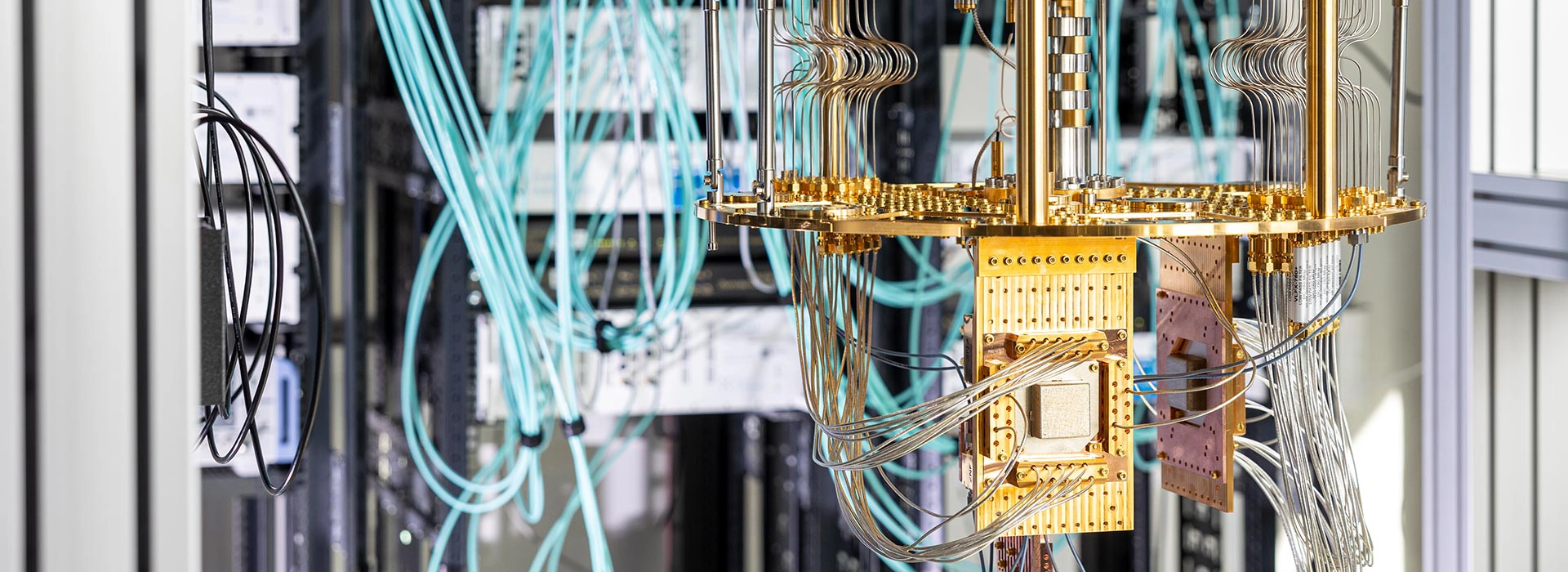

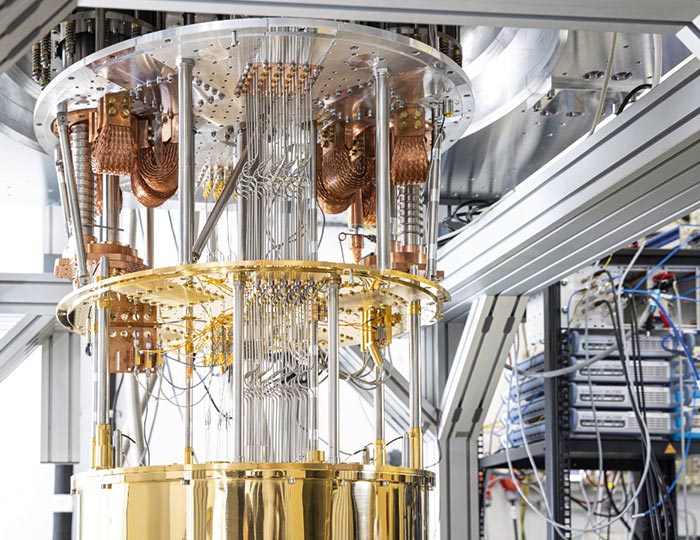

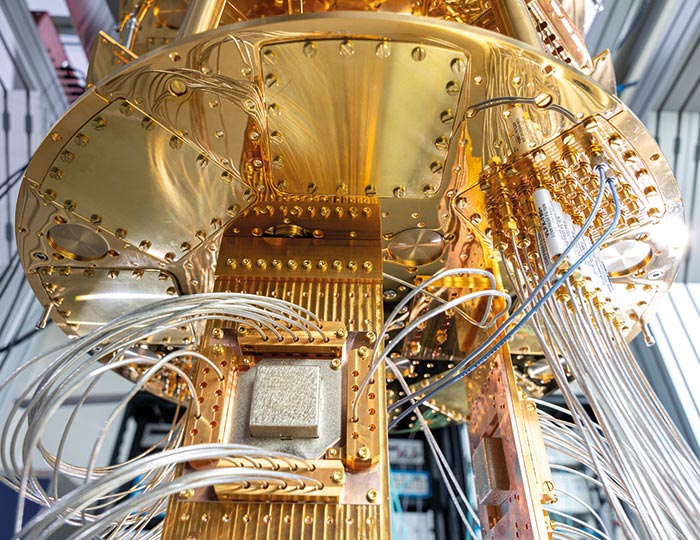

The challenge is to control the qubits at the lower level. The cryostat’s control electronics currently fill entire floors. In order to process the analog signals – to amplify or attenuate them – all coaxial cables are routed out of the cryostat. The extensive wiring in turn conducts heat from the outside to the qubits.

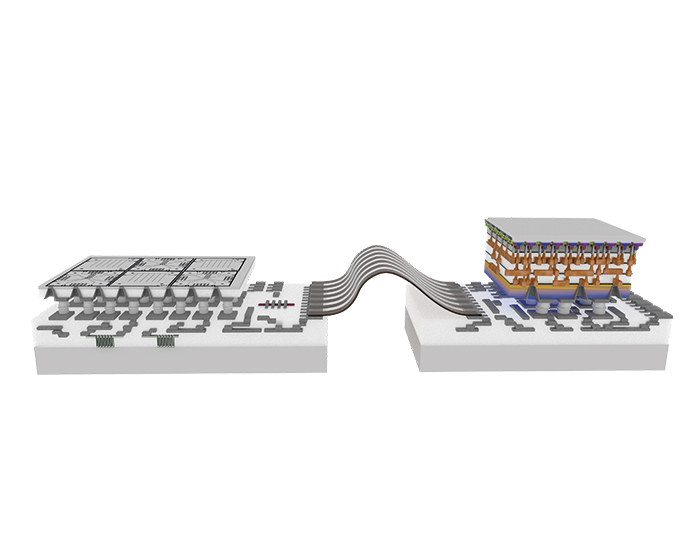

In order to implement more physical qubits, the electronic components for signal control and processing must be integrated directly into the cryogenic environment. | © Fraunhofer IPMS I M. Wislicenus

Under the leadership of Forschungszentrum (FZ) Jülich, 25 German research institutions and companies are working on the joint research project »QSolid« to develop a quantum computer made in Germany with better error rates.

Fraunhofer IZM-ASSID is collaborating with Fraunhofer IPMS and GlobalFoundries to develop interposer technology that focuses on high-density superconducting connections and thermal decoupling through advanced packaging.

Duration: 01/2022 – 12/2026

Funding body: Federal Ministry of Education and Research

Grant number (subproject): 13N16150

Total funding: €76.3 million

Project website

Interposers as a bridge between electronics and cryostats

The basic paradigm is to integrate the control electronics—which are located outside the cryostat—into the future cryostats. »There is a great demand for innovation and a pressure to conduct research in order to make at least parts of the control electronics as compact as possible, covering just a few square centimeters, and to bring them as close as possible to the qubits on a wiring carrier. This is the area where most innovation will be needed in the semiconductor world,« summarizes Bickel.

Left: Cryogenic setup and control of a superconducting quantum computer at Forschungszentrum Jülich; Right: View of the quantum processor, the central processing unit of the QSolid prototype | © Forschungszentrum Jülich / Sascha Kreklau

Si interposers are high-density wiring carriers that form the connection between several chips in an electronic system. The rigid-flex interposer technology developed at Fraunhofer IZM is a promising basis for controlling more than 10,000 qubits. Essentially, the technology promises to combine high wiring densities with thermal decoupling.

»Our contribution to the QSolid project is to build part of the wiring around the quantum chip,« Bickel sums up. The wiring is an important prerequisite for controlling the qubits at their operating temperatures. Fraunhofer IZM-ASSID is supplying the packaging technologies and, together with Fraunhofer IPMS and GlobalFoundries, has developed an interposer technology that transfers a concept from room-temperature electronics to applications at very cold temperatures, using new materials like titanium nitride and ultra-thin layer systems.

The flexible part of the interposer consists of polyimide and superconducting wiring. The colder side with the quantum chip is connected to a cooling stage via a cooling finger, while the control electronics are connected to a more powerful cooling stage due to the need for more cooling. The thermal decoupling between the two subcarriers then prevents the quantum chip from heating up.

Schematic representation of the QSolid interposer with bumps and phononic Bragg reflector | © Fraunhofer IPMS I M. Wislicenus

»A functional proof of the technology is still missing,« explains Bickel. To test the samples, the researchers first have to cool them to around two Kelvin for about a day. They also have to take contamination effects into account and ensure the smooth production of standard materials. »We are taking a relatively conservative approach to the project and are not starting with a revolution. Titanium nitride can be deposited reactively.«

On the way to high-density superconducting wiring carriers

The electrically and thermomechanically stable interposer measures 20 by 15 millimeters. It is the product of extensive development work on deposition and structuring processes. Due to the heat generated during the crystallization of titanium nitride, which can only be dissipated to a limited extent via polyimide, numerous deposition parameters have to be optimized to achieve the right target properties. They include the material composition or the geometry of the layers, some properties can affect other properties again, and processing should happen in the shortest possible time.

Rigid-flex interposers with different polyimide lengths | © Fraunhofer IZM-ASSID

The »QSolid« project is pursuing a semiconductor-based packaging approach that offers a very high level of compatibility with industrial manufacturing processes. »We are preparing a proof of concept to check whether semiconductor-based wiring carriers are compatible with superconducting qubits. The initial results are very promising,« Bickel says about the current status of the project.

»The next step is to demonstrate whether we can scale the process to even higher wiring densities. Coaxial structures are required for high-frequency wiring.« At 20 by 15 millimeters, the interposer is relatively small. Steffen Bickel and his team are therefore working with Forschungszentrum Jülich and RWTH Aachen University to investigate the effects on system behavior when the size of the interposer increases by a factor of 2 or 3 to 40 by 80 millimeters.

Freedom as a driver of innovation in quantum research

»At Fraunhofer IZM in Berlin and Fraunhofer IZM-ASSID in Dresden, we are in a great position to provide the basic technologies needed to build quantum computers with very high wiring densities,« says Bickel. At low temperatures, you also get the requirement for superconductivity is added. Both at room temperature and at these low temperatures, optoelectronics – via waveguides – play an important role.

The potential of the technology and interest in the topic are great. Bickel is often asked how quantum computing will likely move on and what the next steps will be: »This research field has a touch of the untouched about it, because none of us knows exactly what will happen and which technology will ultimately prevail.« In his opinion, venturing into unknown technological territory requires, above all, freedom for research: »Both the funding landscape and the local management at Fraunhofer IZM-ASSID and our institute give us researchers that necessary freedom.«

»It is a great honor for me to be able to participate in the development of quantum computing. Even if it turns out later that our approach is not successful.« Bickel adds that, in retrospect, only the success stories of technological developments are ever told. »See, how many researchers tried to develop a functioning car tire? There were many, unfortunately, that we never hear about.«

Current reports refer to »Q-Day.« This would be the point in time when quantum computers are able to crack conventional encryption systems. »I believe that anyone working in the research and technology industry approaches the issue with optimism.« However, Bickel does not rule out the possibility that new technologies could have an extremely disruptive effect.

Press release, September 18, 2025: »Interposer Technology revolutionizes connections in quantum computers«

Add comment