RealIZM-Blog-Series “Integrative Circular Economy” – Part 1

The average working life of a smartphone among the over-16s in Germany lasts only around 7 to 12 months. Users opt for newer models as a result of the fast innovation cycles, driven by the high competitive pressure on manufacturers, and their own desire for up-to-date systems and better battery life. Often, smartphones are replaced outright, since few repairs or upgrades can be carried out by users, and they are commonly associated with high costs on the part of the retailers. However, circular designs and modular systems offer a viable approach to reducing the environmental impact of all of this.

One project that addressed this issue was the BMBF-funded joint MoDeSt project “Product circularity through modular design – strategies for longer-lasting smartphones“, in which a transdisciplinary consortium investigated the technical, social, and economic factors that decide whether a modular smartphone would be a success.

In this first part of our RealIZM blog series on the “Integrative Circular Economy”, Professor Melanie Jaeger-Erben, sustainability researcher at BTU Cottbus-Senftenberg, gives us an insight into the research methods used in the project as well as the different needs, expectations, and behavior patterns of smartphone users.

E-waste is one of the fastest growing types of waste in the EU. In 2020, the EU Commission therefore presented a new action plan for the circular economy that put particular priority on ways to reduce the flood of e-waste. In order to significantly extend the lifespans of electronic products like smartphones, the materials and the devices they are made from should be repaired, reused, and recycled for as long as possible.

Circular design is one possible solution to drive the green transformation of the economy. The concept goes back to the idea of a circular economy, where raw materials are recycled in such a way that little or no waste is generated or that everything can ultimately be reprocessed. Circular design therefore takes the idea of recyclability into account from the very start. What will the complete product lifecycle look like – and how can it be extended? Based on this, researchers at Fraunhofer IZM have developed a construction kit for circular design principles and made it freely available online to anybody interested in the issue.

One promising approach is the concept of modularity. When asked about this, Professor Jaeger-Erben likes to start by clearing up some concepts:

“A smartphone is already a very modular device in terms of possible applications. You can do an almost infinite number of things with these mini-computers: for example, stream your favorite series, listen to music, plan your daily life, or do your banking. They are ready to use anytime, anywhere. Smartphones are replacing more and more devices like alarm clocks, digital cameras and, in some cases, even desktop computers.”

However, a smartphone is only modular in the strict sense of the circular economy if users can quickly and easily replace individual components (hardware) such as the display or the battery. Which means that the individual components must not be glued in place. Numerous smartphone manufacturers, like Shift GmbH who are involved in the project, are already focusing on making repairs simpler. The EU Commission is even calling for a “right to repair”.

Modularity also means that the hardware and software of a new smartphone must be compatible with older versions and that hardware can be upgraded. In order to significantly improve the functional performance of a smartphone or, for instance, to be able to take better photos, it is necessary from the user’s point of view that the camera, speakers, or storage can be replaced.

Modular smartphones can keep pace with technological progress by being upgraded and meet changing consumer needs at the same time. The key to the success of such concepts is acceptance and interest on the part of the users. Added to this are specific user skills and knowledge of repair or retrofit options.

Are modular smartphones more sustainable per se?

The concept of modularity has advantages and disadvantages on both the software and the hardware levels The goal of the MoDeSt research project was to demonstrate the potential and the limitations of modularity, both technically and economically. Colleagues from Leuphana University Lüneburg investigated various business models, while the team from TU Berlin and Fraunhofer IZM examined the social and societal aspects from the user’s perspective.

In the project, the diverse types of use were scrutinized both in how smartphones are designed and how they are retailed. Several workshops were held and a wide variety of data was collected and analyzed, one of the focus jobs for Fraunhofer IZM, which has many years of expertise in preparing lifecycle and environmental assessments of electronic products. In addition to environmental data that shed light on negative impacts and regulatory requirements, the MoDeSt project also incorporated everyday observations by participants (so-called culture probes).

Culture probes are a way to gain deeper insights and an even better understanding of the needs of the users. The project participants were asked to observe themselves and think creatively about various problems and questions. For example, they were asked to write down what they thought were the “seven deadly sins” of the smartphone, or what their personal family tree of past and present smartphones looks like. This outside-the-box thinking motivated the participants to think more about their everyday use of the smartphone than a conventional interview could have done.

© Prof. Dr. Melanie Jaeger-Erben

How smartphones are used differently

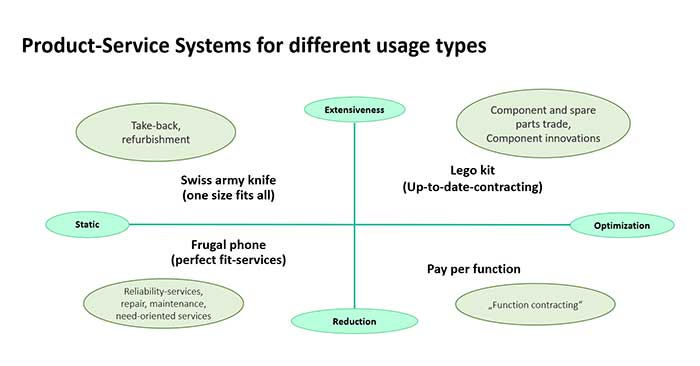

The researchers took a very close look at the everyday use of smartphones. One key finding was that there are very different usage patterns and requirements. A total of four types of use were identified, which differ in terms of the intensity and purpose of smartphone use and the technical skills of the users.

© Prof. Dr. Melanie Jaeger-Erben

There are differences in the intensity of people’s use of their smartphones – from extensive (i.e., online day and night) to sporadic – and in their tech affinity. The range here extends from people permanently optimizing their gear, e.g. reorganizing apps or performing regular updates, to people primarily keeping their smartphones technically stable/unchanged.The researchers were puzzled by the fact that the range of smartphones in the market is so homogeneous when one considers how much diversity and variety there is in how they are actually used.

“Some users who would be satisfied with a minimalistic smartphone get a Swiss army knife with everything on it,” Professor Jaeger-Erben explains. According to the researcher, it would make sense and also be more sustainable if there were different smartphone types for at least four very different types of users. “From the users’ point of view, we would like to see more diversity,” she sums up.

The phenomenon of technical overkill also affects other consumer electronics, such as televisions and notebooks. But how could the one-size-fits-all approach be transformed into a more diverse offering? The researchers assigned suitable business models to each of the four unique usage types, which are reflected in the equipment, services, and also different device designs. In addition to the modular structure and specific design concepts of the devices, the researchers see great leverage on the side of sales. In their opinion, diversity is a strength. Therefore, sales advice tailored to the specific buyer’s needs should already be offered at the time of purchase, and equipment should be adapted to the usage profile.

“In fact, we need product-service combinations that stop users from getting overwhelmed”, Professor Jaeger-Erben summarizes. “One of our conclusions is that significantly more emphasis needs to be placed on enabling modularity, both in terms of repairs, hardware and software updates, and business models.”

For the less tech-savvy among the intensive smartphone users, the one-size-fits-all solution – the Swiss army knife – seems best suited. Although the devices are potentially overequipped and may not be used for long, offering ways to take back and refurbish the devices can still give them a long service life with multiple users in succession.

For intensive smartphone users who exhibit a lot of tech affinity – the so-called optimization seekers – a business model seems suitable that the researchers equate to Lego construction kits. For this user group, the focus should be on device modularity in combination with an update / upgrade contract model. This would allow these power users to switch as soon as new modules are available. The “old” elements are reprocessed and transferred back to the market.

“Frugal users“ who use their smartphones very little or very selectively are generally satisfied with a reduced range of functions. For them, a perfect-fit service in the form of advice and, if necessary, concrete assistance is important. Their main focus is on the reliability of the device.

For the critical enthusiasts, i.e., people who know their way around, but do not want to use their smartphones much, device functionality plays a central role. For them, a “pay-per-function” service would be optimal, where they borrow devices and pay only for the functions they actually use.

Two questions that the researchers found to be very important were

- How willing would users be to give their modular devices up for a short period of time while they are being repaired?

- And are users willing to give up certain functions that cannot be replaced?

In fact, some users tend to prefer to buy a new device, since going without seems unimaginable for them for even short periods like one to three days. Or they temporarily reactivate an older device that is still sitting around in their own household. The offer of a repair service would not work for them.

When asked about the most important finding of the project, Professor Jaeger-Erben explains: “We were able to show that modularity is not a simple fix-it solution for sustainability and longevity. It can only be the means of choice in specific cases.” The decisive factor in ensuring that products such as smartphones are used for longer than they are now – whether by one user or by several generations – is not so much the design, but above all the service.

“Sometimes you get the feeling that the design of an object is held up as the ‘next big thing.’ The main thing is that it’s shiny and photogenic. Instead of focusing on utility, it’s primarily a question of whether a product looks visually new, rather than whether it really satisfies needs better than old equipment. More is invested into marketing than into actually focusing on the needs of the users. In addition, design decisions are still far too rarely human-centered,” Professor Melanie Jaeger-Erben says about the current situation.

She therefore calls for more participation in technology development and inclusive design. Potential users should be involved more often in product and technology development and get to express their needs. In her opinion, the perspective of people with disabilities and senior citizens, who have special requirements for smartphones, is unfortunately ignored far too often.

Instead of addressing only experts, as has been the case in the past, less tech-savvy users should also be accommodated in the future. This is how the idea of working with experienced industrial designers came about in the research project. Based on the usage typologies and their different needs, Tapani Jokinen and Robin Hoske developed two design concepts for smartphones that differ significantly from each other. They worked on the principle that the concept ideas should support the longest possible use of the devices and at the same time improve everyday communication and minimize users’ worries about handling the devices.

A detailed presentation of MODEST CUBE and MODEST ARCH will follow in the next two parts of the RealIZM blog series – save the dates: July 13 and August 3, 2023.

- The joint MoDeSt project was funded by the BMBF as part of the “Resource-efficient circular economy – Innovative product cycles (ReziProK)” initiative.

- Funding code: 033R231

- Duration: 01.07.2019 – 30.06.2022 Participating partners: Fraunhofer IZM, TU Berlin (later BTU Cottbus-Senftenberg), Centre for Sustainability Management (CSM) of Leuphana University Lüneburg, Integrated Quality Design (IQD) of Johannes Kepler University Linz (associated), SHIFT GmbH and AfB gGmbH.

Sources:

Jaeger-Erben, M., Proske, M. & Hielscher, S. (2023, im Druck) Scalability and durability, or is modular the new durable? The case of smartphones. In: Jaeger-Erben, M., Wieser, H., Marwede, M. & Hofmann, F. (2023). Durable Economies – Organising the Material Foundations of Society. transcript Verlag.

Hielscher, S., Jaeger-Erben, M., & Poppe, E. (2020). Modular smartphones and circular design strategies: The shape of things to come?. In The Routledge Handbook of Waste, Resources and the Circular Economy (pp. 337-349). Routledge.

This could be interesting for you:

- Circular Economy – A More Sustainable Journey for Electronic Devices

- How Design Superpowers Will Save Our Planet

- Sustainable mobile devices for the environment: Long live smartphones and tablets!

Subscribe to RealIZM Newsletter!

Get the latest insights into electronic-packaging and innovative technologies in microelectronics deliver